You’ve probably turned a radio dial before, music, news, ads, people talking. It’s all familiar and predictable.

Now imagine landing on a frequencY that feels wrong. There’s no station name, no song, no chatter, no ads. Instead, the broadcast opens with a music box tune, delicate and haunting. Then comes the voice: monotone, counting numbers in a slow, repeating, emotionless cadence. One after another, the digits tumble out with no explanation, no context, no pause.

It sounds like nonsense.

Except it isn’t.

Somewhere, someone is listening for that exact sequence of numbers, at that exact moment.

Welcome to the world of numbers stations, a strange and perhaps unsettling phenomenon of espionage.

Enter the World of Numbers Stations

Imagine a spy named Charlie, sent abroad by his country’s intelligence agency to gather information during a time of war. Before leaving, Charlie receives a small booklet filled with pages of random numbers called a one-time pad (OTP). This booklet is identical to the copy held by his agency, so both Charlie and the agency possess matching pads. Each page is meant to be used once and only once.

Charlie has been working in the field for quite some time when his agency decides it’s time to call him back. They don’t call, email, or use any digital network. Instead, they use a transmitter to broadcast a series of numbers over a high-frequency radio band.

Charlie tunes his shortwave radio to the assigned frequency and waits. A brief signal at the start, made up of familiar tones, confirms the message is meant for him. A call sign follows, then a monotone voice begins counting in an odd, emotionless rhythm: zero four one, followed by five-digit groups, each repeated twice: seven two nine four three, one eight five zero six… seven two nine four three, one eight five zero six. Charlie copies the numbers by hand.

Off the air, he opens page 041 of his one-time pad and performs the arithmetic he has practiced hundreds of times, combining the broadcast numbers with the pad values and converting the result back into letters. The meaningless digits resolve cleanly into two words: COME HOME. He destroys the page immediately.

Charlie takes a moment to marvel at the brilliance of the system, anyone could have heard the broadcast, yet only he could make sense of it. With that thought, he begins preparing for his journey back home.

While Charlie himself is fictional, his story illustrates the core logic of numbers stations and how they operate in practice. Simply put, a numbers station is a radio broadcast that is public, anyone tuned intO the frequency, from casual listeners to hobbyists, can hear it. To most, the transmission sounds random, disjointed, repetitive, and sometimes eerie. Yet hidden within it is an encrypted message, readable only by the spy it was intended for, who alone possesses the identical one-time pad (OTP) needed to decode it.

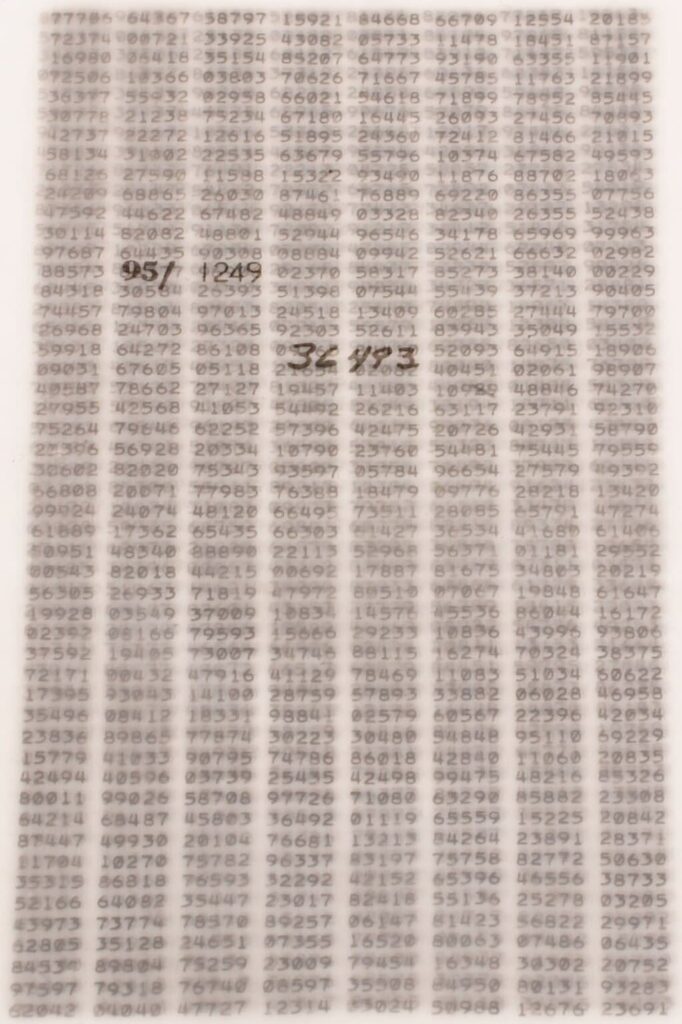

A one-time pad is a booklet filled with truly random numbers. Though it looks like a page of meaningless digits, these numbers are the key to unlocking the broadcast. When an agent receives a transmission, they note the referenced page number, then perform arithmetic on the transmitted number groups using the corresponding numbers on the pad. The resulting values translate into letters, which form the words of the message. Each page of the pad is used only once, and the agent’s copy is identical to the one held by the sending agency. Without the correct OTP page, the broadcast is completely meaningless, no amount of careful listening or recording can reveal its contents.

Photo By: The Central Intelligence Agency, Public domain

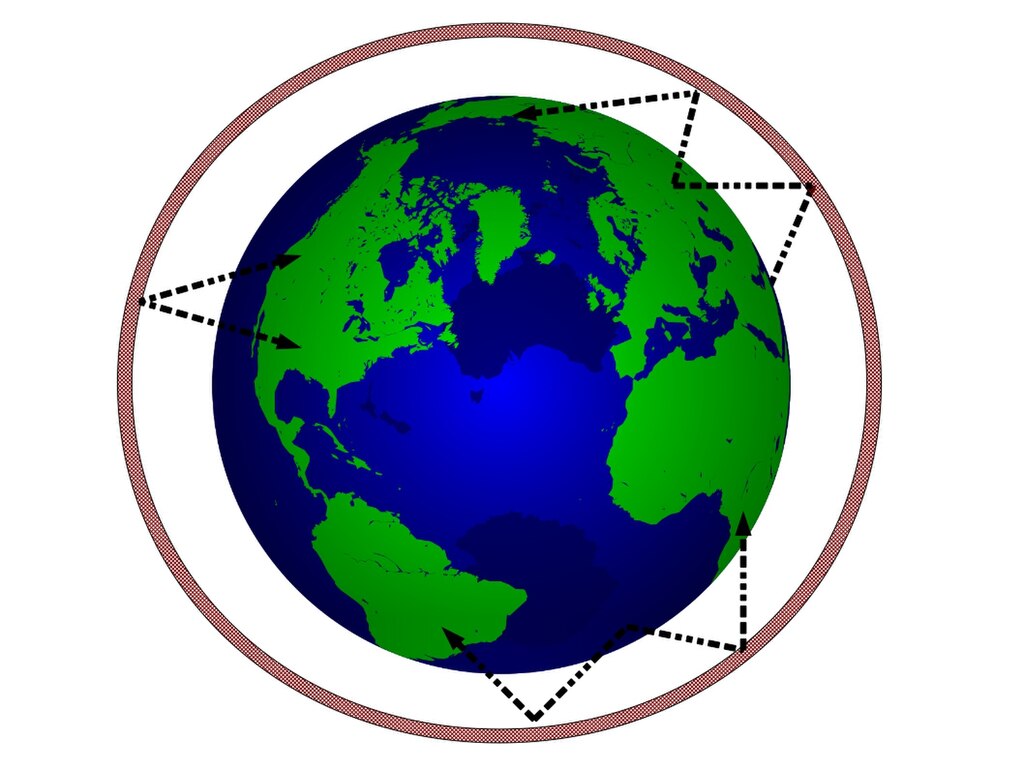

These broadcasts are transmitted over high-frequency (HF) waves, typically spanning 3–30 MHz. HF signals can travel thousands of miles because they reflect off the ionosphere, a charged layer high above Earth. This allows a single broadcast to reach agents across continents without relying on satellites, cables, or other infrastructure. Paired with the OTP, HF radio is ideal for espionage as it is inexpensive, widely available, and entirely passive; it lets an agent listen without transmitting anything or leaving an electronic trace. In other words, the secrecy of the message rests entirely in the key, not in concealing the broadcast itself.

Image By: Kf4yfd, Noldoaran, Augiasstallputzer~commonswiki, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Here’s what a transmission looks like in practice. Each broadcast begins with an identifier, perhaps a series of crisp mechanical beeps, or the faint tinkling strains of a music box, or a low, warbling tone. This signals to the intended agent that the message is meant for them. The main message follows, consisting of groUps of digits, often repeated several times to prevent transcription errors, delivered in a monotone voice that drones with a precise, almost hypnotic rhythm. A fixed sign-off, maybe a fading sequence of zeros, or a haunting musical motif, or a verbal cue, concludes the transmission, confirming its end. These disciplined procedures, combined with the security of the one-time pad and the global reach of HF propagation, allow agencies to communicate securely with their agents while revealing nothing to anyone else monitoring the airwaves.

A single numbers station can serve many agents simultaneously. Each agent listens for a specific identifier and decodes only the message intended for them, using their own pad.

The Rise of Numbers Stations

Numbers stations have roots stretching back to World War I. Early military radio experiments showed that instructions could be sent over long distances without revealing who was listening. German, British, and Russian militaries quickly saw that shortwave broadcasts could deliver orders to agents behind enemy lines while leaving no trace of the listener.

By World War II, several nations had formalized one-way encrypted broadcasts. Germany’s Wehrmacht, Britain’s Special Operations Executive, and the USSR all used these networks to send operational directives to their agents; rendezvous points, sabotage instructions, or logistical updates.

During the Cold War, numbers stations became widespread and systematic. Their growth was driven by three key factors: shortwave radios were cheap and globally accessible; signals could bounce off the ionosphere to reach any continent; and one-way broadcasts left no electronic footprint. Stations oFten transmitted at the same time each day, using call signs, music cues, or signature tones, letting multiple agents pick out different messages from the same broadcast using their own one-time pads.

Despite their ubiquity, governments rarely acknowledged the stations. The first near-official statement came in 1998, when the UK Department of Trade and Industry remarked:

“These [numbers stations] are what you suppose they are. People shouldn’t be mystified by them. They are not for, shall we say, public consumption.

Historical records, declassified files, and amateur recordings confirm that stations like the Lincolnshire Poacher, UVB-76, and Atención were active for decades.

Ghosts on the Air

For decades, numbers statiOns have fascinated radio enthusiasts, who log, record, and obsess over their every detail. These listeners gave these anonymous stations nicknames, often inspired by the stations’ quirks or the eerie melodies that opened the broadcasts.

Take the Lincolnshire Poacher, for example. Each transmission began with the first two bars of an English folk song. Though quaint to an untrained ear, it was instantly recognizable as the start of a coded broadcast. Repeated dozens of times a day, the tiny melody became its ghostly signature.

Or consider Atención, a Cuban station linked to espionage cases. Its voice was monotone and hypnotic, reading nUmbers in a precise, unchanging rhythm. The sequence could go on for hours, with each repetition intended for a different agent somewhere in the world.

Then there was HM01, a station notorious among enthusiasts for its unpredictable behavior. Occasionally, its broadcasts would overlap with other stations on nearby frequencies, producing chaotic collisions of numbers, tones, and static. To hobbyists monitoring the airwaves, it sounded like two voices speaking at once, digits clashing and repeating, creating a puzzle that was impossible to fully untangle. It added aN air of mystery that made HM01 legendary among listeners.

Some transmissions went even further into the realm of the uncanny, earning the label “ghost stations.” These were broadcasts that never seemed to carry actionable instructions, just endless loops of numbers, odd bursts of tones, or sequences drowned in static. Experts and enthusiasts speculate that these stations were deliberately designed to mislead or exhaust casual listeners or rival intelligence services. Tuning in, one could spend hours chasing meaning where there was none, following phantom signals.

Projects like The Conet Project, led by Akin Fernandez, have preserved hundreds of these transmissions from Europe to the Americas. Listening to them today is like stepping into another world.

Collisions on the Airwaves

Numbers stations rarely operated in complete isolation. Their signals sometimes overlapped with other broadcasts, creating chaotic interference, while other overlaps were deliberate attempts to jam or disrupt rival stations. In 2006, North Korea’s Voice of Korea was reported by monitoring enthusiasts to transmit on frequencies formerly used by the Lincolnshire Poacher, possibly to overwrite or confuse listeners tuning in. Similarly, E10, believeD to be Israeli, reportedly experienced deliberate jamming from the Chinese Music Station.

Even without intentional interference, overlapping signals are common in shortwave bands. Multiple stations transmitting at the same hour or on adjacent frequencies could create static, cross-talk, or garbled numbers. UVB-76, the Russian “Buzzer” station, occasionally overlaps with other nearby broadcasts, producing a strange mix of buzzer tones and occasional voice snippets, all documented in The Conet Project recordings. Lincolnshire Poacher’s nearby frequencies were sometimes occupied by other stations, leading hobbyists to note moments of interference.

This unpredictability is partly due to the nature of shortwave propagation. Ionospheric conditions shIft constantly, causing signals to skip, fade in and out, or collide with distant broadcasts on similar frequencies. As a result, each transmission could sound slightly different for listeners worldwide, even if the underlying message remained unchanged. Amateur enthusiasts often described these moments as ghostly or surreal.

Despite these collisions, whether accidental or deliberate, numbers stations remained effective. Their persistence is not nostalgic but practical. In hostile environments, where surveillance is assumed, numbers stations remain a highly resilient method of communication.

As Rupert Allason observed:

“Nobody has found a more convenient and expedient way of communicating with an agent.”

Secrets in Plain Sight

Numbers stations operated in near-total secrecy, but the Cuban Five case brought one, Atención, into public awareness. In the 1990s and early 2000s, a small network of Cuban operatives in the United States relied on shortwave broadcasts to receive instructions. Each broadcast was a monotone recitation of numbers, which the operatives recorded and later decoded using one-time pads, converting sequences of digits into operational directives.

The FBI uncovered the network not by breaking the broadcast itself, but through a combination of physical surveillance, intercepted communications, and operational errors by the agents. Investigators observed meetings between operatives, traced contacts and communications, and documented lapses in operational securiTy. Once arrests were made, authorities seized recorded transmissions, one-time pads, and operational logs. Using these materials, decoding the messages became straightforward.

Court records show that some messages contained routine administrative instructions such as schedules, contacts, and reporting protocols, while others provided operational guidance, including directions to maintain cover, monitor specific targets, or follow surveillance procedures. For investigators, these decoded messages offered a clear view into the operatives’ covert activities.

Importantly, the broadcasts themselves were never compromised. The communication system’s security depended entirely on the physical control of one-time pads; once they were seized, the messages could be decoded.